June 8, 2013, Shasta: Sting of the Tarantula Hawk

6/8/13

US elsewhere

39264

3

It took me a long time to come to terms with my own actions in response to what happened to me this day. And it also took months for me to figure out what insect had actually stung me, so this report is now finally being written in mid-September, over 3 months after the trip. I hope that it doesn't come across as critical of my partners, that's not my intent and is among the main reasons that I've been reluctant to write a TR, and still hesitant to post this even after writing it. But it's a memorable story, definitely among the most unusual events that has happened to me in over 17 years and 700 days of backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering, and a unique trip in other ways too due to the very high freezing level and full ski ascent. Maybe there's something useful in the story for others, and certainly analyzing and writing about the incident has been cathartic for me.

June 8, 2013, Mount Shasta: Stunning Sting of the Tarantula Hawk

(plus a summit ski ascent & descent via the Hotlum-Wintun route)

"The pain is like an electric wand that hits you, inducing an immediate, excruciating pain that simply shuts down ones ability to do anything, except, perhaps, scream. Mental discipline simply does not work in these situations."

-- entomologist Dr.

We had left the 7200 ft Brewer Creek trailhead just before 6am, hiking the bare trail for less than a mile to reach continuous snow at 7650 ft and then skinning from there. It felt nice to have the weight of the skis and boots off my back and below the feet instead, gliding smoothly up the gentle sun-warmed slopes, and everything seemed just great.

Skinning towards treeline, about 20 minutes before the sting. (photo by DB)

It was 7:20am and we were ascending past treeline near 8800 ft. My six partners this day, three women and three men from Bend and from Seattle, trailed just a few ski lengths behind me, each of us engrossed in our thoughts or conversations.

Skinning up, just a minute or two before the sting.

Suddenly a black object, almost a shadow of sorts and perhaps 1-2 inches long, flew in from the corner of my vision, glanced off my right thumb in what seemed like an instant, and vanished away into the distance. What the #$%^!!! Like a lightning bolt, the electric wand had struck me, right through the PL100 glove liner protecting my hand from the morning chill. In a flash the pain overwhelmed me. Still skinning upward, I collapsed immediately onto my knees, supported from prostration only by the bindings attaching my boot toes to the stable platform of my skis -- and like Dr. Schmidt quoted above, I was unable to do anything but scream, a stream of F-words all I could muster at that moment.

Within seconds, still on my knees, I realized that I must have been stung by some type of bee or wasp, but I had no idea what kind it could possibly have been to cause this degree of pain and sudden collapse -- all I had seen was a black shadowy object, maybe an inch or two in length. I've been stung by bees or wasps numerous times before, most recently in August 2010 during a solo ski ascent and descent of Mount Baker (

It took a while before I was able to began skinning again though, perhaps 10 minutes after the sting, and I knew by then that things were not completely OK. I soon noticed that my fingers, toes, and lips were all beginning to feel numb, and my pace had slowed dramatically. Prior to the sting, we'd been moving uphill at a brisk pace of about 1600 vertical feet per hour despite the flatness of the slope, and I had been near the front of the group -- now I was struggling to do even 1200 feet per hour and falling far behind the group, which was becoming tinier with each passing minute.

I was still in considerable pain, my extremities were going numb, and now I was quite annoyed too, feeling forsaken and left behind -- but there was nothing I could do except keep striding uphill towards my vanishing partners. The numbness in my fingers and toes was spreading slowly up each limb, my feet soon felt almost completely numb from the ankles forward, and both hands too, making it difficult to grip the ski poles (I always use straps held in the proper grip, which helped a lot in this case). Most tellingly of all, the numbness was advancing much farther up my left arm (the opposite side) than my right arm (the one which got stung). To the scientist in me, this had an obvious explanation: I had suffered a fairly massive envenomation of some type, and my heart was pumping the venom throughout my body, including preferentially to the nearer left arm than the right -- even more so given the high cardiac output needed to skin uphill at elevations passing 10000 ft. (Months later, when I finally figured out what insect had most likely stung me, this seemingly bizarre set of symptoms would all make more sense.)

Thankfully, my partners had taken a break at a flattish bench near 10300 ft and waited for me, but it seemed to take forever to slowly reach them. Almost 90 minutes had now passed since the sting (the times listed here are based on my continual photo-taking, which serves as a digital diary of my trips). The numbness was still spreading up my limbs, and I was in a very foul mood -- unfortunately I lashed out at my partners, especially the one who was my closest friend in the group, for not having even one person stay behind with me. I told them that I didn't want to stop, that I'd be safer out in front of them rather than being left far behind, since they had been moving so much faster than I could after the sting. I did mention my worsening symptoms to them, especially the increasing numbness, but in my pain-addled state of mind I never really considered turning around. (To this day, I still regret my petulant behavior towards my partners, they had no way of knowing how bad this sting really was, and I don't blame them for continuing ahead. But I've always felt strongly that in the mountains, the slowest member of a group, whether slow due to injury or fitness or whatever, should never be left alone far to the rear.)

So I left the others at their break spot and kept shuffling slowly onward. As I continued skinning onward and upward, the numbness incrementally advanced farther up each limb, and I realized that things were likely to proceed in one of two ways: either the numbness (and perhaps partial paralysis) would continue to increase and I would soon be incapacitated, maybe eventually collapsing to the snow in a heap -- or the venom might begin to be metabolized and neutralized, and things might improve. As long as I could still skin, I was determined to just keep going, and at the time, I was not even considering how foolish this might be. It was reassuring to know that there were partners behind me to help in case of emergency, and I'm not certain that I would have continued up had I been solo this day (as I often am, especially on volcano-hopping road trips far from Seattle).

At 11200 ft, I traversed left through the only available all-snow crossover from the Hotlum-Wintun snowfield over to the Wintun Glacier (the higher crossover above 12400 ft was already bare this year). Over 2 hours had now passed since the sting, and my left arm was numb nearly to the shoulder, the right to just below the elbow, both feet back to the ankles, and much of my lips too. But I could still keep robotically skinning upward, sliding the skis and planting the poles.

And soon I had a new goal which steeled my resolve to continue upward: a full ski ascent of Mount Shasta from snowline to the summit, something which I had never yet managed to do despite 23 previous summit ski descents since 1999. Most backcountry skiers don't seem to care about ski ascents, but for me, I almost value them more than the ski descents. It's certainly much more difficult to complete a full ski ascent of any of the high Cascade volcanoes (and most other major mountains) than it is to do a full ski descent given modern gear, and full ski ascents are in general quite rarely done compared to ski descents, especially so on the two 14000 ft monarchs of the Cascade Range, Mounts Rainier and Shasta. On Rainier, I've managed only twice to do complete ski ascents (out of 24 summit ski descents), once via . But none at all on Shasta -- every previous time, the combination of steepness (all summit ski routes reach or exceed 35-40 degrees at some point) and firm snow conditions during the morning ascents had thwarted me even with ski crampons, forcing the skis onto my pack for some portion of the climb, often thousands of feet. Only 6 days earlier, I had switched to foot crampons at 11200 ft and booted the remaining 3000 ft to the summit, the snow much too firm for efficient or safe skinning.

Zoomed view from just after we started skinning, showing the upper Hotlum-Wintun route.

But this day was different: the forecast freezing level of 16500 ft was the highest I had ever had on Shasta, and as far as I can recall, the 2nd highest of any ski trip I've ever done (trailing only the 18000 ft freezing level I experienced on

Two-shot panorama, another party postholes the skin track as my partners skin up towards me at 13000 ft.

With my unexpectedly superpower-enhanced speed, I was now far above my partners (who had also crossed a long section of bare talus at 12400 ft after missing the all-snow crossing lower down), so I decided to wait for them at 13000 ft. The warm day meant that I had almost finished my 2.5 liters of water, so there was time to melt another 1.5 liters on the Jetboil while I waited. By the time they caught up it was almost 11:20am, 4 hours since the sting, and they were relieved to hear that my symptoms were now improving, along with my mood.

The several other ski and snowboard parties on the route had all switched over to booting, which was mostly a mess of deep postholing in the intensely sun-softened snow with no good-quality bootpack in place (I had lamented the lack of a proper bootpack during my previous ascent 6 days earlier, too). We continued up on skins, thankful to be avoiding the postholing, and I was glad to have a couple of the other guys in our group take over trail breaking duties for the next stretch.

Eventually near 13600 ft the route steepens to about 40 degrees, and the ski penetration increased to 6" in the oversoftened mush, raising the risk of wet sluffs. But it felt solid enough to me and I took over the lead the rest of the way, the adrenaline rush of the long-sought full ski ascent combined with the fading pain and numbness to spur me onward. The mushy snow remained stable the whole way with no slipping or sluffing. The snow and the skinning extended all the way up to over 14150 ft, and I arrived at the summit rocks at 12:30pm, stoked to finally have skinned up Mount Shasta for the first time after so many years.

The others followed just a few minutes behind, and some of us even continued undaunted for a few more yards past the snow, but the last few yards of the summit block were bare as they usually are in late spring and summer. The temperature at the summit was in the mid 40s, but a cool NW breeze of 10-20 mph kept it a bit chilly despite the intense sunshine. We all gathered at the summit, celebrated the first time up Shasta for some in our group, rested for awhile and took some photos.

As the group returned to the snow's edge and prepared to ski, I felt energetic and decided to do a quick hike along the ridge to the lower north summit (14120+ ft). However my fingers and toes still remained somewhat numb at this point, almost 6 hours after the sting.

Six-shot panorama looking back at the main summit (left) from the ridge to the north summit (far right), with the 14040+ ft west summit at center. (click for double-size version)

The views looking down the north and northwest side were outstanding, the satellite cone of Shastina with its blue meltwater crater lakes and the heavily crevassed Whitney Glacier below it. I had not been over to this north summit in at least 8 years, but should definitely make sure to walk over there much more often when I ski Shasta in the future.

Two-shot panorama looking down on Shastina and the Whitney Glacier from the north summit.

(continued below)

June 8, 2013, Mount Shasta: Stunning Sting of the Tarantula Hawk

(plus a summit ski ascent & descent via the Hotlum-Wintun route)

"The pain is like an electric wand that hits you, inducing an immediate, excruciating pain that simply shuts down ones ability to do anything, except, perhaps, scream. Mental discipline simply does not work in these situations."

-- entomologist Dr.

We had left the 7200 ft Brewer Creek trailhead just before 6am, hiking the bare trail for less than a mile to reach continuous snow at 7650 ft and then skinning from there. It felt nice to have the weight of the skis and boots off my back and below the feet instead, gliding smoothly up the gentle sun-warmed slopes, and everything seemed just great.

Skinning towards treeline, about 20 minutes before the sting. (photo by DB)

It was 7:20am and we were ascending past treeline near 8800 ft. My six partners this day, three women and three men from Bend and from Seattle, trailed just a few ski lengths behind me, each of us engrossed in our thoughts or conversations.

Skinning up, just a minute or two before the sting.

Suddenly a black object, almost a shadow of sorts and perhaps 1-2 inches long, flew in from the corner of my vision, glanced off my right thumb in what seemed like an instant, and vanished away into the distance. What the #$%^!!! Like a lightning bolt, the electric wand had struck me, right through the PL100 glove liner protecting my hand from the morning chill. In a flash the pain overwhelmed me. Still skinning upward, I collapsed immediately onto my knees, supported from prostration only by the bindings attaching my boot toes to the stable platform of my skis -- and like Dr. Schmidt quoted above, I was unable to do anything but scream, a stream of F-words all I could muster at that moment.

Within seconds, still on my knees, I realized that I must have been stung by some type of bee or wasp, but I had no idea what kind it could possibly have been to cause this degree of pain and sudden collapse -- all I had seen was a black shadowy object, maybe an inch or two in length. I've been stung by bees or wasps numerous times before, most recently in August 2010 during a solo ski ascent and descent of Mount Baker (

It took a while before I was able to began skinning again though, perhaps 10 minutes after the sting, and I knew by then that things were not completely OK. I soon noticed that my fingers, toes, and lips were all beginning to feel numb, and my pace had slowed dramatically. Prior to the sting, we'd been moving uphill at a brisk pace of about 1600 vertical feet per hour despite the flatness of the slope, and I had been near the front of the group -- now I was struggling to do even 1200 feet per hour and falling far behind the group, which was becoming tinier with each passing minute.

I was still in considerable pain, my extremities were going numb, and now I was quite annoyed too, feeling forsaken and left behind -- but there was nothing I could do except keep striding uphill towards my vanishing partners. The numbness in my fingers and toes was spreading slowly up each limb, my feet soon felt almost completely numb from the ankles forward, and both hands too, making it difficult to grip the ski poles (I always use straps held in the proper grip, which helped a lot in this case). Most tellingly of all, the numbness was advancing much farther up my left arm (the opposite side) than my right arm (the one which got stung). To the scientist in me, this had an obvious explanation: I had suffered a fairly massive envenomation of some type, and my heart was pumping the venom throughout my body, including preferentially to the nearer left arm than the right -- even more so given the high cardiac output needed to skin uphill at elevations passing 10000 ft. (Months later, when I finally figured out what insect had most likely stung me, this seemingly bizarre set of symptoms would all make more sense.)

Thankfully, my partners had taken a break at a flattish bench near 10300 ft and waited for me, but it seemed to take forever to slowly reach them. Almost 90 minutes had now passed since the sting (the times listed here are based on my continual photo-taking, which serves as a digital diary of my trips). The numbness was still spreading up my limbs, and I was in a very foul mood -- unfortunately I lashed out at my partners, especially the one who was my closest friend in the group, for not having even one person stay behind with me. I told them that I didn't want to stop, that I'd be safer out in front of them rather than being left far behind, since they had been moving so much faster than I could after the sting. I did mention my worsening symptoms to them, especially the increasing numbness, but in my pain-addled state of mind I never really considered turning around. (To this day, I still regret my petulant behavior towards my partners, they had no way of knowing how bad this sting really was, and I don't blame them for continuing ahead. But I've always felt strongly that in the mountains, the slowest member of a group, whether slow due to injury or fitness or whatever, should never be left alone far to the rear.)

So I left the others at their break spot and kept shuffling slowly onward. As I continued skinning onward and upward, the numbness incrementally advanced farther up each limb, and I realized that things were likely to proceed in one of two ways: either the numbness (and perhaps partial paralysis) would continue to increase and I would soon be incapacitated, maybe eventually collapsing to the snow in a heap -- or the venom might begin to be metabolized and neutralized, and things might improve. As long as I could still skin, I was determined to just keep going, and at the time, I was not even considering how foolish this might be. It was reassuring to know that there were partners behind me to help in case of emergency, and I'm not certain that I would have continued up had I been solo this day (as I often am, especially on volcano-hopping road trips far from Seattle).

At 11200 ft, I traversed left through the only available all-snow crossover from the Hotlum-Wintun snowfield over to the Wintun Glacier (the higher crossover above 12400 ft was already bare this year). Over 2 hours had now passed since the sting, and my left arm was numb nearly to the shoulder, the right to just below the elbow, both feet back to the ankles, and much of my lips too. But I could still keep robotically skinning upward, sliding the skis and planting the poles.

And soon I had a new goal which steeled my resolve to continue upward: a full ski ascent of Mount Shasta from snowline to the summit, something which I had never yet managed to do despite 23 previous summit ski descents since 1999. Most backcountry skiers don't seem to care about ski ascents, but for me, I almost value them more than the ski descents. It's certainly much more difficult to complete a full ski ascent of any of the high Cascade volcanoes (and most other major mountains) than it is to do a full ski descent given modern gear, and full ski ascents are in general quite rarely done compared to ski descents, especially so on the two 14000 ft monarchs of the Cascade Range, Mounts Rainier and Shasta. On Rainier, I've managed only twice to do complete ski ascents (out of 24 summit ski descents), once via . But none at all on Shasta -- every previous time, the combination of steepness (all summit ski routes reach or exceed 35-40 degrees at some point) and firm snow conditions during the morning ascents had thwarted me even with ski crampons, forcing the skis onto my pack for some portion of the climb, often thousands of feet. Only 6 days earlier, I had switched to foot crampons at 11200 ft and booted the remaining 3000 ft to the summit, the snow much too firm for efficient or safe skinning.

Zoomed view from just after we started skinning, showing the upper Hotlum-Wintun route.

But this day was different: the forecast freezing level of 16500 ft was the highest I had ever had on Shasta, and as far as I can recall, the 2nd highest of any ski trip I've ever done (trailing only the 18000 ft freezing level I experienced on

Two-shot panorama, another party postholes the skin track as my partners skin up towards me at 13000 ft.

With my unexpectedly superpower-enhanced speed, I was now far above my partners (who had also crossed a long section of bare talus at 12400 ft after missing the all-snow crossing lower down), so I decided to wait for them at 13000 ft. The warm day meant that I had almost finished my 2.5 liters of water, so there was time to melt another 1.5 liters on the Jetboil while I waited. By the time they caught up it was almost 11:20am, 4 hours since the sting, and they were relieved to hear that my symptoms were now improving, along with my mood.

The several other ski and snowboard parties on the route had all switched over to booting, which was mostly a mess of deep postholing in the intensely sun-softened snow with no good-quality bootpack in place (I had lamented the lack of a proper bootpack during my previous ascent 6 days earlier, too). We continued up on skins, thankful to be avoiding the postholing, and I was glad to have a couple of the other guys in our group take over trail breaking duties for the next stretch.

Eventually near 13600 ft the route steepens to about 40 degrees, and the ski penetration increased to 6" in the oversoftened mush, raising the risk of wet sluffs. But it felt solid enough to me and I took over the lead the rest of the way, the adrenaline rush of the long-sought full ski ascent combined with the fading pain and numbness to spur me onward. The mushy snow remained stable the whole way with no slipping or sluffing. The snow and the skinning extended all the way up to over 14150 ft, and I arrived at the summit rocks at 12:30pm, stoked to finally have skinned up Mount Shasta for the first time after so many years.

The others followed just a few minutes behind, and some of us even continued undaunted for a few more yards past the snow, but the last few yards of the summit block were bare as they usually are in late spring and summer. The temperature at the summit was in the mid 40s, but a cool NW breeze of 10-20 mph kept it a bit chilly despite the intense sunshine. We all gathered at the summit, celebrated the first time up Shasta for some in our group, rested for awhile and took some photos.

As the group returned to the snow's edge and prepared to ski, I felt energetic and decided to do a quick hike along the ridge to the lower north summit (14120+ ft). However my fingers and toes still remained somewhat numb at this point, almost 6 hours after the sting.

Six-shot panorama looking back at the main summit (left) from the ridge to the north summit (far right), with the 14040+ ft west summit at center. (click for double-size version)

The views looking down the north and northwest side were outstanding, the satellite cone of Shastina with its blue meltwater crater lakes and the heavily crevassed Whitney Glacier below it. I had not been over to this north summit in at least 8 years, but should definitely make sure to walk over there much more often when I ski Shasta in the future.

Two-shot panorama looking down on Shastina and the Whitney Glacier from the north summit.

(continued below)

At long last it was time to ski, a bit after 1pm now. The snow conditions were fairly good, mostly corn, but obviously oversoftened in places given the high temperatures and late hour. The uppermost couple feet of snow had fallen about 10 days earlier, and although fairly well consolidated during the sunny weather since the last storms, it was still not fully consolidated into summerlike condition. The steep slope directly below the summit was sluffing a bit as we skied, making things slightly worrisome for those still ascending. Nothing too big or dangerous slid though, just a few inches deep of surface sluff. So a few of us cut way over to skier's right at the first opening through the rocky ridge, onto the southern lobe of the Wintun Glacier, where the snow was much smoother and almost untracked.

Two-shot panorama / multiple exposure of skiing the upper Wintun Glacier, with Lassen Peak on the horizon.

Two-shot panorama / multiple exposure of skiing smooth soft corn on the upper Wintun Glacier.

I decided to keep skiing that fall line, down to where the snow ended near 11200 ft in a gully above a waterfall. But it would have been possible to ski all the way down to 9000 ft or lower by going even farther right, through the fairly-crevassed (but passable) Wintun icefall and on down past the terminus of the Wintun Glacier.

[img width=1000 height=300">http://www.skimountaineer.com/TR/Images2013/ShastaWintunGlacierPano2000-08Jun2013.jpg" />

Four-shot panorama looking down onto the lower Wintun Glacier from about 12000 ft. (click for double-size version)

I really wanted to ski the entire length of the Wintun, which I'd never done before, but it felt like too much risk for me to try that solo on this day (no others were interested). Plus that descent would have required a lot of effort to exit from and get back to the trailhead, which would have meant leaving my partners stuck waiting a few hours for me at the car (the best choice would have been to reascend that entire route, 3000+ ft of extra ascent, instead of traversing in ski boots across miles of pumice and ash). Nevertheless, I was glad to have recovered enough from the morning sting to feel like I had the energy to consider it, even though such a lengthy reascent would have put the total vert for the day around 10000 ft. As it was, I skinned up about 700 vert from where I turned around, back partway up the upper Wintun Glacier to where it was an easy angle to rejoin the morning ascent route and thus ski back more directly towards the trailhead.

Although the heat and high freezing level had noticeably thinned a few sections of snow down low in the trees, it was still possible to ski and shuffle all the way back down to 7650 ft where we had left our shoes and skinned from in the morning. A total of about 7200 vert of skiing for 7700 ft of gain, not a bad ratio at all in June given the far-below-normal snowpack throughout California this season -- the snow coverage at this time was similar to early July of a typical year.

A quick 20 minute walk brought me back to the cars just before 4pm, about a half-hour after my partners who were chilling in the shade with some beers. By now I was almost fully recovered from the sting, but some residual numbness still remained in my fingers and toes almost 9 hours after the incident. On the drive back north to Bend, we snapped a few good photos of the Hotlum-Wintun route and the northeast side of Shasta from the pumice flat along FR 19 a few miles north of the Brewer Creek turnoff.

Zoomed view from the pumice flat of Wintun Glacier (left), Hotlum-Wintun ridge (center), and Hotlum Glacier (right) with a prominent lava flow below it.

And about an hour later we were enjoying excellent beer and burgers at Klamath Basin Brewing in Klamath Falls. Don't miss the outstanding vanilla porter!

So the mystery still remained: what insect had stung me? It seemed obvious that it had to be some type of bee or wasp (which includes hornets and yellow jackets), but attempting to Google the answer later that day as soon as I had internet access on my phone proved fruitless. My symptoms were not those of anaphylactic shock at all, nor was there any swelling of any kind whatsoever (not even a bump at the location of the sting), so it didn't match standard symptoms listed for bee or wasp stings.

Here is the very limited information I had to base my search on:

* Unknown bee or wasp, probably black, maybe 1-2 inches long

* Sting produces intense full-body pain, but no swelling at site of sting

* Venom causes numbness or partial paralysis in the limbs and extremities for some time

Repeated attempts to research the answer online over the next few days and weeks were fruitless -- there is just not much info at all about the specific differences in symptoms of being stung by the hundreds of various different genera of wasps and bees (with many thousands of total species). Nor did I get a good look at (or even better, have a good photo or the body of) the actual insect that stung me, so I was definitely searching blind. Trying to look in published field guides was even more fruitless, their coverage of bee and wasp species was far too limited (even in the few "Insects of North America" field guides). There are just too many kinds of bees and wasps out there. Very frustrating to not be able to find any answers after much effort searching, even though I did read and learn a lot about bees and wasps, it was to no avail and eventually I stopped thinking about it too much.

But it was always in the back of my mind, both the mystery hymenopteran insect that had stung me, and my actions after the sting. A few days ago I began to read about wasps again, and this time quite suddenly, the answer seemed perfectly clear and obvious: it was almost certainly a tarantula hawk, a type of large spider wasp. I'd heard of tarantula hawks before, especially because they are noted for having a sting which is among the most painful of any insect (see Starr sting pain scale and Schmidt sting pain index), but never initially imagined that one of them could be what stung me. However, I realized that the pain I experienced matched almost exactly with Schmidt's description quoted above (at the start of the first post), and that spurred me to research this more thoroughly.

Photo from Wikipedia of a typical tarantula hawk (Pepsis formosa) taken in northern California.

Tarantula hawks are members of the genera Pepsis or Hemipepsis, which together include over 300 species, about 25 of which have a range that extends north of Mexico into the western United States. The females attack and paralyze a much larger spider or tarantula using their potent venom and then deposit an egg onto the abdomen of the victim; the egg hatches into a larva which burrows into the still-living spider, slowly consuming it from within over several weeks as it grows and metamorphoses several times, until finally emerging as a new adult wasp. As with all types of bees and wasps, only the females are capable of stinging, and despite the carnivory of the larva (technically it is a parasitoid), adult tarantula hawks of both sexes feed not by predation but on nectar from flowers. Unlike most bees and the better-known social wasps like yellow jackets, the tarantula hawks are solitary wasps and do not have a communal hive or nest.

Photo from Wikipedia of a tarantula hawk dragging an envenomed tarantula across the ground.

"Tarantula hawks produce large quantities of venom and their stings produce immediate, intense, excruciating short term pain in envenomed humans. Although the instantaneous pain of a tarantula hawk sting is the greatest recorded for any stinging insect, the venom itself lacks meaningful vertebrate toxicity ... the defensive value of stings and venom of these species is based entirely upon pain. This pain confers near absolute protection from vertebrate predators."

-- Schmidt, J.O. 2004. Venom and the Good Life in Tarantula Hawks (see references below)

Tarantula hawks are not generally aggressive towards humans, but stings do nevertheless occur. Why one would suddenly fly onto my thumb (while I was skinning uphill in a large open area just above treeline) and sting me with no apparent provocation of any kind is a mystery with no likely answer.

These are the key parameters of tarantula hawks that match the insect involved in my incident:

* Range covers almost all of California (and much of the western U.S.), including the Mount Shasta region

* East side of Mount Shasta has the proper type of habitat, arid semi-desert with sandy soil and large clearings in open forest

* Large size, about 1-2 inches long, and most species have a black or dark bluish-black body

* Very long stinger, up to 3/8 inch, sufficient to effortlessly penetrate through the liner glove I was wearing

* Potent venom, with a sting that produces excruciating pain, but no significant swelling

* My initial pain matches almost exactly Schmidt's description of their sting

* The worst of the pain lasts for only several minutes, not hours as in the case of some other hymenopteran stings

* Very large amount of venom per sting, equivalent to tens of honey bee stings (which themselves are noted for large amount of venom compared to other stings)

* Venom is paralytic in its effects, but not very toxic nor fatal, especially for vertebrates

Photo from Bug Eric of Hemipepsis ustulata taken in Colorado.

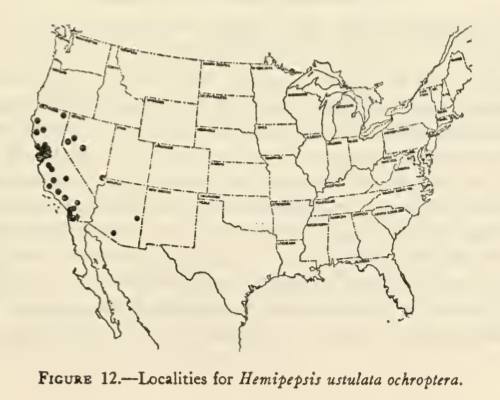

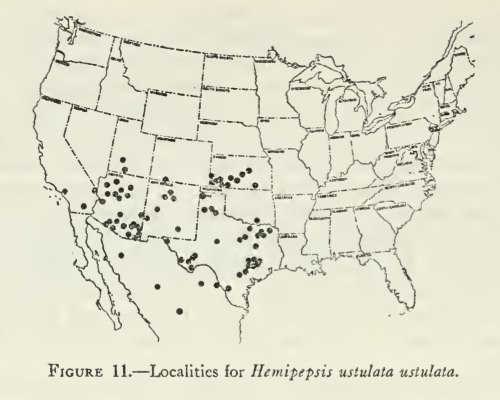

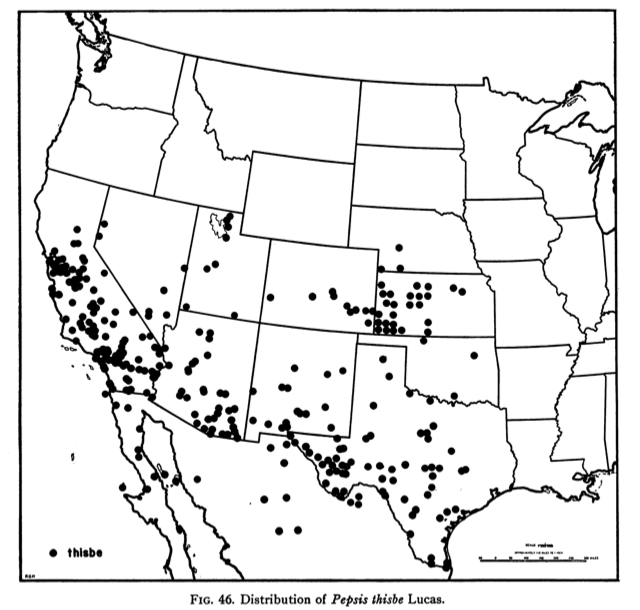

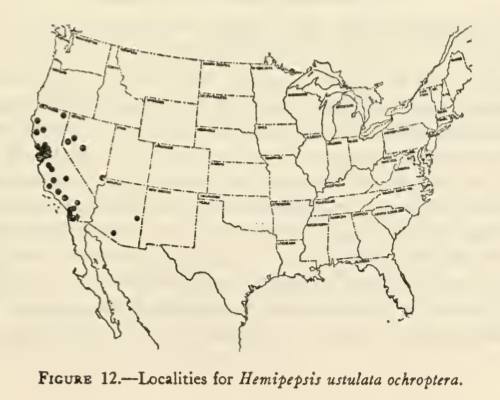

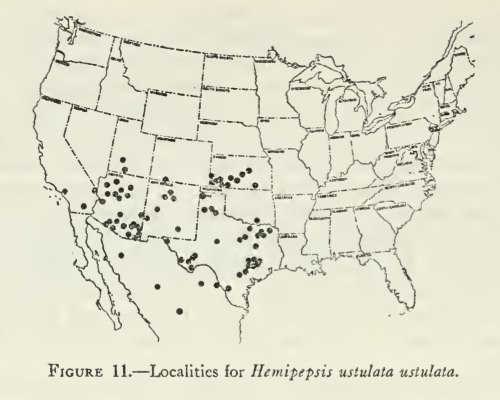

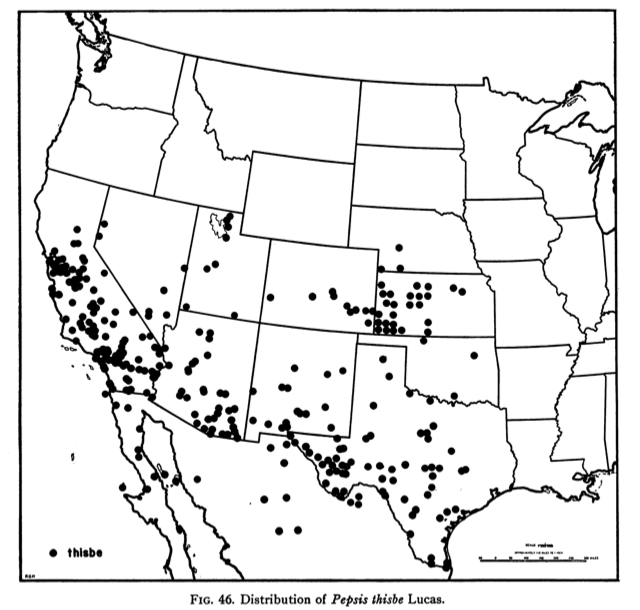

Without a closeup photo or the body of the insect, there's no way to determine what particular species it might have been, or even to know for certain that it was a member of the Pepsis or Hemipepsis genera. But given the well-matching parameters listed above, a tarantula hawk certainly seems to be the most likely candidate among all the possible bee or wasp species that live in the region. Based on the (very incomplete) range maps that are available for the various tarantula hawk species, the most likely species may be Hemipepsis ustulata, whose widespread range includes all of northeastern California including the Mount Shasta region (for the Hemipepsis ustulata ochroptera subspecies). This area is just north of the typical range of several Pepsis species. The range of Pepsis thisbe extends north into the southernmost Cascades, while Pepsis mildei and Pepsis pallidolimbata reach north of Lake Tahoe.

Range maps from Townes 1957 (see references below).

Range map from Hurd 1952 (see references below).

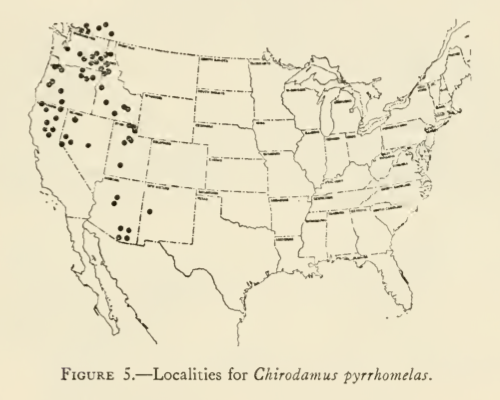

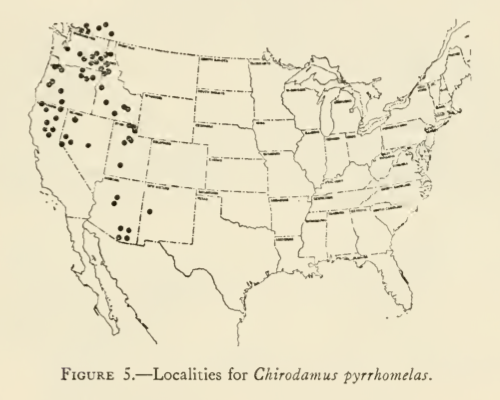

Another possibility may be Calopompilus pyrrhomelas (syn. Chirodamus pyrrhomelas), a spider wasp which is closely related to the tarantula hawks of Pepsis and Hemipepsis (it is in the same subfamily, Pepsinae, and the same tribe, Pepsini). To a casual observer it looks very similar, it also can be over 1 inch long, and its range extends throughout much of the Pacific Northwest from northern California through all of Oregon and Washington, and into central BC. Very little information is available about C. pyrrhomelas or its sting, but it is likely to be as formidable as most other large spider wasps. Several dozen other smaller spider wasp species in about a dozen other genera are also found in northern California.

Photo from BugGuide of Calopompilus pyrrhomelas taken on Mount Eddy, just a few miles west of Mount Shasta.

Range map from Townes 1957 (see references below).

Tarantula hawks (and other spider wasps) are fascinating creatures, and it was interesting to learn so much about them during my quest for answers. Here are some of the references that were useful in my research:

Hurd Jr., P. D. 1952. Revision of the Nearctic species of the pompilid genus Pepsis (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 98:260–334.

(free PDF: http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/handle/2246/1025?show=full)

Williams, F. X. 1956. Life history studies of Pepsis and Hemipepsis wasps in California (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 49(5):447–466.

(excellent paper with detailed photos and descriptions of their fascinating life cycle -- unfortunately, does not appear to be available for free online, see http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/esa/aesa/1956/00000049/00000005/art00005, but UW library has it)

Townes, H.K. 1957. Nearctic wasps of the subfamilies Pepsinae and Ceropalinae. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 209:1-286.

(useful range maps for many species, see p. 19 for C. pyrrhomelas and p. 37 for Hemipepsis ustulata; free PDF or read online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/33144)

Evans, H. E., and M. J. West-Eberhard. 1970. The Wasps. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. vi + 265 pp.

Wasbauer, M. S. and L. S. Kimsey. 1985. California Spider Wasps of the Subfamily Pompilinae (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 26:1-130

(info and range maps for dozens of other spider wasp species in CA, free PDF: http://essig.berkeley.edu/documents/cis/cis26.pdf)

Schmidt, J. O. 1990. Hymenopteran venoms: striving toward the ultimate defense against vertebrates. In D. L. Evans and J. O. Schmidt (eds.). Insect Defense: Adaptations and Strategies of Prey and Predators, pp. 387–419. State University of New York Press, Albany, New York. xv + 482 pp.

Evans, H. E. 1997. Spider wasps of Colorado (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae): an annotated checklist. The Great Basin Naturalist 57:189-197.

(free PDF: https://ojs.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/wnan/article/view/28304)

Vardy, C.R. 2000. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 1. Introduction and the P. rubra species-group. Zoologische Verhandelingen 332:1-86

Vardy, C.R. 2002. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 2. The P. grossa- to P. deaurata-groups. Zoologische Verhandelingen 338:1-134

Vardy, C.R. 2005. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 3. The P. inclyta- to P. auriguttata-groups. Zoologische Mededelingen 79:1-305

(free PDFs of all 3 parts: http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/cgi/b/bib/bib-idx?type=simple&c=naturalis&rgn1=entire+record&q1=tarantula-hawk)

Schmidt, J.O. 2004. Venom and the Good Life in Tarantula Hawks: How to Eat, Not be Eaten, and Live Long. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 77:402-413.

(read the full article online for free with registration at http://www.jstor.org/stable/25086231)

Bug Eric: Hemipepsis ustulata

Genus Pepsis - Tarantula Hawks - BugGuide.Net

Genus Hemipepsis - Tarantula Hawks - BugGuide.Net

Genus Calopompilus - BugGuide.Net

[tt">FORECAST FOR MOUNT SHASTA RECREATIONAL AREA

NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE MEDFORD, OR

308 AM PDT SAT JUN 8 2013

TODAY...SUNNY. HIGHS IN THE LOWER TO MID 80S. NORTHEAST WINDS 10 TO 15 MPH.

TONIGHT...MOSTLY CLEAR. LOWS IN THE MID 50S TO LOWER 60S. NORTH WINDS 10 TO 15 MPH.

SUNDAY...SUNNY IN THE MORNING...THEN PARTLY CLOUDY WITH A 20 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS IN THE AFTERNOON. HIGHS IN THE LOWER TO MID 80S. NORTHEAST WINDS 5 TO 10 MPH SHIFTING TO THE NORTHWEST IN THE AFTERNOON.

SUNDAY NIGHT...COOLER. PARTLY CLOUDY IN THE EVENING THEN BECOMING MOSTLY CLOUDY. A 30 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS. LOWS IN THE MID 40S TO MID 50S.

MONDAY...COOLER. PARTLY CLOUDY WITH A 20 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS. HIGHS AROUND 70.

EXTENDED...

TUESDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS IN THE 40S. HIGHS 65 TO 75.

WEDNESDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

THURSDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

FRIDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

TODAY TEMPERATURE / WIND (MPH)

6000 FEET 83 / NE 12

10000 FEET 66 / NE 14

14000 FEET 48 / N 13

SNOW LEVEL FORECAST

TODAY.......... 15400 FEET <<< [b">Note:[/b"> As it says, these are snow levels, so the freezing level

TONIGHT........ 15300 FEET is roughly 1000 ft higher, about 16500 ft on this day!

SUNDAY......... 15200 FEET (which matches the freezing level predicted by the UW model)

SUNDAY NIGHT... 14500 FEET

MONDAY......... 12900 FEET

[/tt">

Other reports from the same trip (TRs may be written at some point):

May 31, 2013, Mt Rainier, Muir Snowfield POWDER

June 1, 2013, Lassen Peak, West Face via Southeast Face, plus Eagle Peak

June 2, 2013, Mt Shasta, Hotlum-Wintun with Wintun Gully Descent

June 3, 2013, Mt Bachelor, Sunset Ski of Northwest Face via North Ridge

June 5, 2013, South Sister, Double Summit Traverse: West Ridge & Lost Creek Glacier via South Ridge & Lewis Glacier

June 6, 2013, Mt Bachelor, Sunset Ski of Northwest Face via Summit Express Route

June 8, 2013, Mt Shasta, this report

June 10, 2013, Mt Adams, Avalanche Glacier Headwall via South Butte, Gotchen Glacier & Mazama Glacier

Two-shot panorama / multiple exposure of skiing the upper Wintun Glacier, with Lassen Peak on the horizon.

Two-shot panorama / multiple exposure of skiing smooth soft corn on the upper Wintun Glacier.

I decided to keep skiing that fall line, down to where the snow ended near 11200 ft in a gully above a waterfall. But it would have been possible to ski all the way down to 9000 ft or lower by going even farther right, through the fairly-crevassed (but passable) Wintun icefall and on down past the terminus of the Wintun Glacier.

[img width=1000 height=300">http://www.skimountaineer.com/TR/Images2013/ShastaWintunGlacierPano2000-08Jun2013.jpg" />

Four-shot panorama looking down onto the lower Wintun Glacier from about 12000 ft. (click for double-size version)

I really wanted to ski the entire length of the Wintun, which I'd never done before, but it felt like too much risk for me to try that solo on this day (no others were interested). Plus that descent would have required a lot of effort to exit from and get back to the trailhead, which would have meant leaving my partners stuck waiting a few hours for me at the car (the best choice would have been to reascend that entire route, 3000+ ft of extra ascent, instead of traversing in ski boots across miles of pumice and ash). Nevertheless, I was glad to have recovered enough from the morning sting to feel like I had the energy to consider it, even though such a lengthy reascent would have put the total vert for the day around 10000 ft. As it was, I skinned up about 700 vert from where I turned around, back partway up the upper Wintun Glacier to where it was an easy angle to rejoin the morning ascent route and thus ski back more directly towards the trailhead.

Although the heat and high freezing level had noticeably thinned a few sections of snow down low in the trees, it was still possible to ski and shuffle all the way back down to 7650 ft where we had left our shoes and skinned from in the morning. A total of about 7200 vert of skiing for 7700 ft of gain, not a bad ratio at all in June given the far-below-normal snowpack throughout California this season -- the snow coverage at this time was similar to early July of a typical year.

A quick 20 minute walk brought me back to the cars just before 4pm, about a half-hour after my partners who were chilling in the shade with some beers. By now I was almost fully recovered from the sting, but some residual numbness still remained in my fingers and toes almost 9 hours after the incident. On the drive back north to Bend, we snapped a few good photos of the Hotlum-Wintun route and the northeast side of Shasta from the pumice flat along FR 19 a few miles north of the Brewer Creek turnoff.

Zoomed view from the pumice flat of Wintun Glacier (left), Hotlum-Wintun ridge (center), and Hotlum Glacier (right) with a prominent lava flow below it.

And about an hour later we were enjoying excellent beer and burgers at Klamath Basin Brewing in Klamath Falls. Don't miss the outstanding vanilla porter!

So the mystery still remained: what insect had stung me? It seemed obvious that it had to be some type of bee or wasp (which includes hornets and yellow jackets), but attempting to Google the answer later that day as soon as I had internet access on my phone proved fruitless. My symptoms were not those of anaphylactic shock at all, nor was there any swelling of any kind whatsoever (not even a bump at the location of the sting), so it didn't match standard symptoms listed for bee or wasp stings.

Here is the very limited information I had to base my search on:

* Unknown bee or wasp, probably black, maybe 1-2 inches long

* Sting produces intense full-body pain, but no swelling at site of sting

* Venom causes numbness or partial paralysis in the limbs and extremities for some time

Repeated attempts to research the answer online over the next few days and weeks were fruitless -- there is just not much info at all about the specific differences in symptoms of being stung by the hundreds of various different genera of wasps and bees (with many thousands of total species). Nor did I get a good look at (or even better, have a good photo or the body of) the actual insect that stung me, so I was definitely searching blind. Trying to look in published field guides was even more fruitless, their coverage of bee and wasp species was far too limited (even in the few "Insects of North America" field guides). There are just too many kinds of bees and wasps out there. Very frustrating to not be able to find any answers after much effort searching, even though I did read and learn a lot about bees and wasps, it was to no avail and eventually I stopped thinking about it too much.

But it was always in the back of my mind, both the mystery hymenopteran insect that had stung me, and my actions after the sting. A few days ago I began to read about wasps again, and this time quite suddenly, the answer seemed perfectly clear and obvious: it was almost certainly a tarantula hawk, a type of large spider wasp. I'd heard of tarantula hawks before, especially because they are noted for having a sting which is among the most painful of any insect (see Starr sting pain scale and Schmidt sting pain index), but never initially imagined that one of them could be what stung me. However, I realized that the pain I experienced matched almost exactly with Schmidt's description quoted above (at the start of the first post), and that spurred me to research this more thoroughly.

Photo from Wikipedia of a typical tarantula hawk (Pepsis formosa) taken in northern California.

Tarantula hawks are members of the genera Pepsis or Hemipepsis, which together include over 300 species, about 25 of which have a range that extends north of Mexico into the western United States. The females attack and paralyze a much larger spider or tarantula using their potent venom and then deposit an egg onto the abdomen of the victim; the egg hatches into a larva which burrows into the still-living spider, slowly consuming it from within over several weeks as it grows and metamorphoses several times, until finally emerging as a new adult wasp. As with all types of bees and wasps, only the females are capable of stinging, and despite the carnivory of the larva (technically it is a parasitoid), adult tarantula hawks of both sexes feed not by predation but on nectar from flowers. Unlike most bees and the better-known social wasps like yellow jackets, the tarantula hawks are solitary wasps and do not have a communal hive or nest.

Photo from Wikipedia of a tarantula hawk dragging an envenomed tarantula across the ground.

"Tarantula hawks produce large quantities of venom and their stings produce immediate, intense, excruciating short term pain in envenomed humans. Although the instantaneous pain of a tarantula hawk sting is the greatest recorded for any stinging insect, the venom itself lacks meaningful vertebrate toxicity ... the defensive value of stings and venom of these species is based entirely upon pain. This pain confers near absolute protection from vertebrate predators."

-- Schmidt, J.O. 2004. Venom and the Good Life in Tarantula Hawks (see references below)

Tarantula hawks are not generally aggressive towards humans, but stings do nevertheless occur. Why one would suddenly fly onto my thumb (while I was skinning uphill in a large open area just above treeline) and sting me with no apparent provocation of any kind is a mystery with no likely answer.

These are the key parameters of tarantula hawks that match the insect involved in my incident:

* Range covers almost all of California (and much of the western U.S.), including the Mount Shasta region

* East side of Mount Shasta has the proper type of habitat, arid semi-desert with sandy soil and large clearings in open forest

* Large size, about 1-2 inches long, and most species have a black or dark bluish-black body

* Very long stinger, up to 3/8 inch, sufficient to effortlessly penetrate through the liner glove I was wearing

* Potent venom, with a sting that produces excruciating pain, but no significant swelling

* My initial pain matches almost exactly Schmidt's description of their sting

* The worst of the pain lasts for only several minutes, not hours as in the case of some other hymenopteran stings

* Very large amount of venom per sting, equivalent to tens of honey bee stings (which themselves are noted for large amount of venom compared to other stings)

* Venom is paralytic in its effects, but not very toxic nor fatal, especially for vertebrates

Photo from Bug Eric of Hemipepsis ustulata taken in Colorado.

Without a closeup photo or the body of the insect, there's no way to determine what particular species it might have been, or even to know for certain that it was a member of the Pepsis or Hemipepsis genera. But given the well-matching parameters listed above, a tarantula hawk certainly seems to be the most likely candidate among all the possible bee or wasp species that live in the region. Based on the (very incomplete) range maps that are available for the various tarantula hawk species, the most likely species may be Hemipepsis ustulata, whose widespread range includes all of northeastern California including the Mount Shasta region (for the Hemipepsis ustulata ochroptera subspecies). This area is just north of the typical range of several Pepsis species. The range of Pepsis thisbe extends north into the southernmost Cascades, while Pepsis mildei and Pepsis pallidolimbata reach north of Lake Tahoe.

Range maps from Townes 1957 (see references below).

Range map from Hurd 1952 (see references below).

Another possibility may be Calopompilus pyrrhomelas (syn. Chirodamus pyrrhomelas), a spider wasp which is closely related to the tarantula hawks of Pepsis and Hemipepsis (it is in the same subfamily, Pepsinae, and the same tribe, Pepsini). To a casual observer it looks very similar, it also can be over 1 inch long, and its range extends throughout much of the Pacific Northwest from northern California through all of Oregon and Washington, and into central BC. Very little information is available about C. pyrrhomelas or its sting, but it is likely to be as formidable as most other large spider wasps. Several dozen other smaller spider wasp species in about a dozen other genera are also found in northern California.

Photo from BugGuide of Calopompilus pyrrhomelas taken on Mount Eddy, just a few miles west of Mount Shasta.

Range map from Townes 1957 (see references below).

Tarantula hawks (and other spider wasps) are fascinating creatures, and it was interesting to learn so much about them during my quest for answers. Here are some of the references that were useful in my research:

Hurd Jr., P. D. 1952. Revision of the Nearctic species of the pompilid genus Pepsis (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 98:260–334.

(free PDF: http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/handle/2246/1025?show=full)

Williams, F. X. 1956. Life history studies of Pepsis and Hemipepsis wasps in California (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 49(5):447–466.

(excellent paper with detailed photos and descriptions of their fascinating life cycle -- unfortunately, does not appear to be available for free online, see http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/esa/aesa/1956/00000049/00000005/art00005, but UW library has it)

Townes, H.K. 1957. Nearctic wasps of the subfamilies Pepsinae and Ceropalinae. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 209:1-286.

(useful range maps for many species, see p. 19 for C. pyrrhomelas and p. 37 for Hemipepsis ustulata; free PDF or read online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/33144)

Evans, H. E., and M. J. West-Eberhard. 1970. The Wasps. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. vi + 265 pp.

Wasbauer, M. S. and L. S. Kimsey. 1985. California Spider Wasps of the Subfamily Pompilinae (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 26:1-130

(info and range maps for dozens of other spider wasp species in CA, free PDF: http://essig.berkeley.edu/documents/cis/cis26.pdf)

Schmidt, J. O. 1990. Hymenopteran venoms: striving toward the ultimate defense against vertebrates. In D. L. Evans and J. O. Schmidt (eds.). Insect Defense: Adaptations and Strategies of Prey and Predators, pp. 387–419. State University of New York Press, Albany, New York. xv + 482 pp.

Evans, H. E. 1997. Spider wasps of Colorado (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae): an annotated checklist. The Great Basin Naturalist 57:189-197.

(free PDF: https://ojs.lib.byu.edu/spc/index.php/wnan/article/view/28304)

Vardy, C.R. 2000. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 1. Introduction and the P. rubra species-group. Zoologische Verhandelingen 332:1-86

Vardy, C.R. 2002. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 2. The P. grossa- to P. deaurata-groups. Zoologische Verhandelingen 338:1-134

Vardy, C.R. 2005. The New World tarantula-hawk wasp genus Pepsis Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae). Part 3. The P. inclyta- to P. auriguttata-groups. Zoologische Mededelingen 79:1-305

(free PDFs of all 3 parts: http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/cgi/b/bib/bib-idx?type=simple&c=naturalis&rgn1=entire+record&q1=tarantula-hawk)

Schmidt, J.O. 2004. Venom and the Good Life in Tarantula Hawks: How to Eat, Not be Eaten, and Live Long. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 77:402-413.

(read the full article online for free with registration at http://www.jstor.org/stable/25086231)

Bug Eric: Hemipepsis ustulata

Genus Pepsis - Tarantula Hawks - BugGuide.Net

Genus Hemipepsis - Tarantula Hawks - BugGuide.Net

Genus Calopompilus - BugGuide.Net

[tt">FORECAST FOR MOUNT SHASTA RECREATIONAL AREA

NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE MEDFORD, OR

308 AM PDT SAT JUN 8 2013

TODAY...SUNNY. HIGHS IN THE LOWER TO MID 80S. NORTHEAST WINDS 10 TO 15 MPH.

TONIGHT...MOSTLY CLEAR. LOWS IN THE MID 50S TO LOWER 60S. NORTH WINDS 10 TO 15 MPH.

SUNDAY...SUNNY IN THE MORNING...THEN PARTLY CLOUDY WITH A 20 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS IN THE AFTERNOON. HIGHS IN THE LOWER TO MID 80S. NORTHEAST WINDS 5 TO 10 MPH SHIFTING TO THE NORTHWEST IN THE AFTERNOON.

SUNDAY NIGHT...COOLER. PARTLY CLOUDY IN THE EVENING THEN BECOMING MOSTLY CLOUDY. A 30 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS. LOWS IN THE MID 40S TO MID 50S.

MONDAY...COOLER. PARTLY CLOUDY WITH A 20 PERCENT CHANCE OF THUNDERSTORMS. HIGHS AROUND 70.

EXTENDED...

TUESDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS IN THE 40S. HIGHS 65 TO 75.

WEDNESDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

THURSDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

FRIDAY...PARTLY CLOUDY. LOWS 35 TO 45. HIGHS IN THE 60S.

TODAY TEMPERATURE / WIND (MPH)

6000 FEET 83 / NE 12

10000 FEET 66 / NE 14

14000 FEET 48 / N 13

SNOW LEVEL FORECAST

TODAY.......... 15400 FEET <<< [b">Note:[/b"> As it says, these are snow levels, so the freezing level

TONIGHT........ 15300 FEET is roughly 1000 ft higher, about 16500 ft on this day!

SUNDAY......... 15200 FEET (which matches the freezing level predicted by the UW model)

SUNDAY NIGHT... 14500 FEET

MONDAY......... 12900 FEET

[/tt">

Other reports from the same trip (TRs may be written at some point):

May 31, 2013, Mt Rainier, Muir Snowfield POWDER

June 1, 2013, Lassen Peak, West Face via Southeast Face, plus Eagle Peak

June 2, 2013, Mt Shasta, Hotlum-Wintun with Wintun Gully Descent

June 3, 2013, Mt Bachelor, Sunset Ski of Northwest Face via North Ridge

June 5, 2013, South Sister, Double Summit Traverse: West Ridge & Lost Creek Glacier via South Ridge & Lewis Glacier

June 6, 2013, Mt Bachelor, Sunset Ski of Northwest Face via Summit Express Route

June 8, 2013, Mt Shasta, this report

June 10, 2013, Mt Adams, Avalanche Glacier Headwall via South Butte, Gotchen Glacier & Mazama Glacier

I always thought you looked like a tarantula, esp with the sun hat & whippets. The tarantula hawk was probably just a little hung over, having double vision, doubled your two legs & two whippets, shrunk your size, and whala! tarantula! MUST STING!! So a question still remains...do you feel like you're being consumed by a larva from the inside? Maybe it's taking longer since you're actually much larger than a tarantula? I want to be far away when that thing comes out of you!

Really glad you wrote this TR, it certainly sorts some things out & makes sense of the day. And now I further understand how tough you really are!

Really glad you wrote this TR, it certainly sorts some things out & makes sense of the day. And now I further understand how tough you really are!

Thank you for another informative TR, Amar. Wow, I learned a ton.

Reply to this TR

Please login first: